June 22, 2022 — by: Alicia Bigica

More than $5.2 million in new, unused DMTs were collected from patients with MS over the course of 1 year—from only 1 neuroimmunologist.

Darin Okuda, MD

Nearly every person with a chronic health condition likely has the same voicemail recording on their phone… “Hello Mr. Smith, it’s your local pharmacy. Your 3-month prescription refill is now ready for pick-up.”

Like so many medications meant to address chronic diseases, disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for multiple sclerosis (MS) are often doled out in batches, with patients often receiving 30-day or 3-month refills in close succession.

Convenient? Sure. But we also know that patients struggle with medication compliance and persistence, particularly in the face of tolerability issues.

With nearly 2 dozen approved MS DMTs now available, switching drugs – whether due to patient preference, side effects, cost, efficacy, or otherwise—happens often. But what happens to that 6-month supply of an injectable DMT that’s sitting in Mr. Smith’s hall closet? It stays there. Or worse, it gets tossed out with the rest of the household trash.

The problem may be far greater than most clinicians realize.

“The magnitude of unused DMTs from people with MS has never been quantified and the impact of such therapies in the context of the overall economic burden of care in MS remains poorly understood,” Darin T. Okuda, MD, professor of neurology and director of Neuroinnovation and the Multiple Sclerosis & Neuroimmunology Imaging Program at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, and colleagues wrote. “Despite wide-spread concern about the costs of DMTs in MS, the true prevalence of the problem of wasted medication remains.”

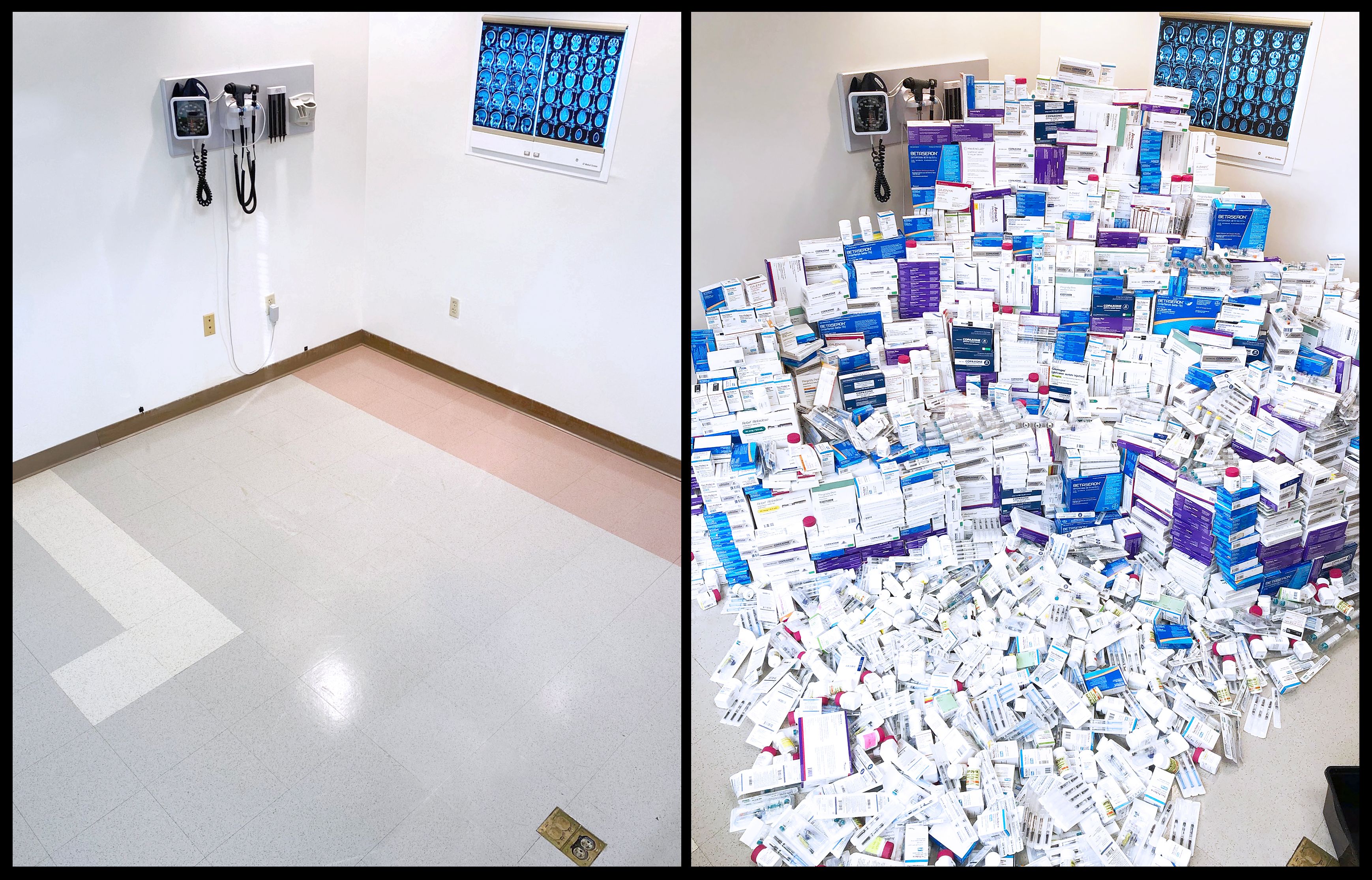

Watching the phenomenon first-hand, investigators led by Okuda set out to quantify just how much DMT waste was occurring and why. What they weren’t prepared for was to fill an exam room of an MS clinic with millions of dollars’ worth of unused, life-altering drugs in a matter of months.

Pictured: A dramatic before and after of the collection of unused DMTs from patients with MS being treated in a single MS clinic. With no buyback policies in place, drugs that are dispensed to consumers can no longer be returned for redistribution due to rules around “chain of custody.”

Image courtesy Darin T. Okuda, MD.

The findings suggest a much more pervasive problem than what is visible at the surface, implying that a one-size-fits-all approach to treatment counseling and patient education may not be sufficient, especially in underserved populations and those at greater risk for more aggressive disease based on race or ethnicity.

“This not only represents a mechanism for reducing medical waste, but also emphasizes the necessity for enhanced education and mindful communication with patients to ensure proper management and long-term care,” Okuda and colleagues wrote.

To better understand the problem, Okuda and colleagues launched a single-center study that included new and existing patients seen in the clinic from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2018, during which patients voluntarily disposed of their FDA-approved DMTs within the clinic. Participants could complete an optional survey about treatment experience and therapy transition, with discontinuation data captured via comprehensive questionnaire. In addition, Okuda and colleagues conducted a 1-month prospective study between November 1, 2018, and December 1, 2018, during which a more pronounced push to collect unused DMTs occurred, with all participating patients required to complete a comprehensive survey that included information on past clinical history and reasoning for treatment transitions.

=======================

Stay informed with MS news and information - Sign-up here

For MS patients, caregivers or clinicians, Care to chat about MS? Join Our online COMMUNITY CHAT