December 25, 2014 /

December 25, 2014

Recently people have been asking me to tell them what is happening with Anti-Lingo and so, below, you can read the most recent information that I could find on this subject.

BIIB033, a monoclonal antibody targeting the LINGO-1 remyelination signaling block, passes phase 1 safety tests

BIIB033, a monoclonal antibody targeting the LINGO-1 remyelination signaling block, passes phase 1 safety tests

CAROL CRUZAN MORTON

A high-profile experimental treatment to repair the damaged myelin around nerves in people with multiple sclerosis (MS) has passed its first clinical testing milestone. The drug, a monoclonal antibody called BIIB033 (Biogen Idec), is safe and tolerable in people, according to the combined results of two phase 1 clinical trials that tested high doses in healthy people and in people with MS.

“We have now reached a potential turning point in MS therapeutics,” according to an editorial published online August 27 with the phase 1 study results in the journalNeurology, Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation (Brugarolas et al., 2014; Tran et al., 2014).

“The anti-LINGO-1 trial is likely the first of many that will test drugs that have been shown to enhance remyelination in [mouse] models,” wrote Pedro Brugarolas, Ph.D., and Brian Popko, Ph.D., of the University of Chicago, Illinois, in the editorial. “Soon we should know whether this approach will provide benefit to patients with MS, which would be the first evidence that enhancing myelin repair may alter the course of this disease.”

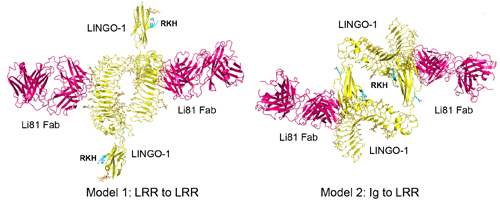

The antibody Li81 (BIIB033, Biogen) in hot pink binds to the signaling molecule LINGO-1 (yellow) in an unexpected four-way structure to induce myelination, shown here in two potential configurations. Image courtesy of Sha Mi and the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (Pepinsky et al., 2014).

With no proven treatments for the progressive forms of MS that cause severe disability, attention has become riveted on ways to repair and restore the myelin that surrounds and protects axons from neurodegeneration (Franklin et al., 2014).

An estimated 2 million people have MS worldwide, including about 450,000 in the United States. Most people are diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, marked by disabling episodes of immune activity, often followed by increasing disability. The 11 U.S.-approved treatments for MS reduce immune damage to the myelin and axons in seven different ways, but there is little evidence they reduce disease progress and long-term disability.

The phase 1 clinical studies of BIIB033 tested an experimental drug that restores myelin in mice. Generally, for remyelination to occur, oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) must survive, multiply, migrate to the lesion, and transform into mature oligodendrocytes that encircle axons with compact myelin sheaths. In MS, OPCs seem to be abundant in lesions but unable to differentiate. Animal and cell studies show that BIIB033 works at this final stage. It shuts down a signaling molecule, LINGO-1, that normally blocks OPCs from differentiating into myelin-making cells (Mi et al., 2004; Pepinski et al., 2014).

In one study that ended in October 2011, 72 healthy people were randomized, with three-quarters receiving a single injection of the drug and the others a placebo. In the other study that finished in April 2012, 47 people with relapsing-remitting MS or secondary progressive MS were randomized, with twice as many receiving the drug as placebo, most of whom receive two injections about two weeks apart. In both groups, participants received escalating doses up to 100 mg/kg.

The researchers had expected a large dose would be necessary for a sufficient amount of the drug to reach the CNS, author Diego Cadavid, M.D., told MSDF in an interview. “It’s a large molecule,” said Cadavid, the medical director for the anti-LINGO-1 development program at Biogen Idec in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “The blood-brain barrier limits the movement of large molecules.”

“Surprisingly, in this study, the concentration of BIIB033 in the [cerebrospinal fluid] did not appear to correlate with the dose administered,” Brugarolas and Popko wrote in the editorial.

Named SYNERGY and launched 1 year ago, it tests four BIIB033 doses ranging from 3 mg/kg to 100 mg/kg, given as an infusion every 4 weeks. The phase 2 study includes once-weekly injections of interferon β-1a (Avonex, Biogen) for people in both the experimental and placebo arms.

In another finding from the phase 1 studies, the authors found a low rate of antibody production, which indicates an immune response that makes the drug ineffective. But they also found antibodies in a placebo-treated person. “A better assay may be needed,” the editorial writers observed.

Other side effects were mild to moderate, unrelated to the drug, and similar in people who received the placebo. Side effects included headaches, upper respiratory infections, and urinary tract infections. No serious side effects or deaths were reported. The drug did not detectably worsen the disease in people with MS.

The next big question for BIIB033 is: Does it work in people? The SYNERGY trial and those for other potential remyelination drugs face an unusual hurdle. “A big problem in the field, a Catch-22, is that we don’t have a good trial design for detecting remyelination,” said neuroradiologist and neurologist Daniel Reich, M.D., Ph.D., chief of the translational neuroradiology unit at the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, in an interview with MSDF. “And we don’t have [a known] remyelinating drug with which to test remyelinating study design. Every trial will be testing both the drug and the trial design. You’ve got to hit them both to get a positive result. That’s tough.”

The phase 1 studies also tested candidate MRI techniques to measure remyelination that have also been deployed to capture secondary outcomes in the phase 2 trial, Cadavid pointed out to MSDF. One helpful data set that emerged was the results of two to three MRIs taken on healthy individuals over 1 month as a reference, he said.

Reich is skeptical about the ability of the nonconventional MRI techniques, magnetization transfer and diffusion tensor imaging, to measure remyelination directly. On the other hand, he thinks that conventional MRI measures will be helpful in clinical trials to show normalized signals consistent with remyelination.

Cadavid’s group will present a poster at the upcoming joint ACTRIMS-ECTRIMSmeeting in Boston that will show other potential CSF biomarkers of remyelination. “It’s important to mention that the target, LINGO-1, is only expressed in the CNS,” he told MSDF. Peripheral biomarkers, such as blood and urine, are irrelevant, he said.

LINGO-1 is abundantly produced by neurons, as well as expressed by oligodendrocytes, and the signaling molecule increases in inflammatory lesions, Cadavid said. “We are testing whether blocking LINGO-1 leads to remyelination in MS.”

Article SOURCE found here

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

.

.

.

Visit our MS Learning Channel on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/msviewsandnews

Stay informed with MS news and information - Sign-up here

For MS patients, caregivers or clinicians, Care to chat about MS? Join Our online COMMUNITY CHAT