Nov 4, 2014

In a mashup of data sets and new genome-mapping tools, a study finds that most of the inherited risk for autoimmune disease discovered so far comes from mysterious noncoding regions and mostly affects immune cells

In a mashup of data sets and new genome-mapping tools, a study finds that most of the inherited risk for autoimmune disease discovered so far comes from mysterious noncoding regions and mostly affects immune cells

CAROL CRUZAN MORTON

Since 2007, ever larger and more powerful genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have found over 150 genetic variants that are more common in people with multiple sclerosis (MS), compared to those who do not have the disabling inflammatory disease of the brain and spinal cord. But there’s a catch.

That impressive number refers mostly to signposts marking chunks of chromosomes where researchers have assumed a guilty gene lurks. The risk from each variant is low, but in an unlucky mix they can add up. The reason for doing GWAS hasn’t changed: Find the specific genetic variants, explore the contributing molecular pathways, and develop better therapies tailored to the disease.

But an uncomfortable question has crept into the discussion about exactly how to pinpoint the culprits.

“What if we find them, and they’re not in the genes?” That’s one of the questions Alexander Marson, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues asked 5 years ago when they launched their study. It doesn’t take a computational biologist to figure those odds. Protein-coding genes make up about 2% of the human genome. Although researchers have only begun to probe the secrets of the vast noncoding regions, their mysterious functions seem to be important in health.

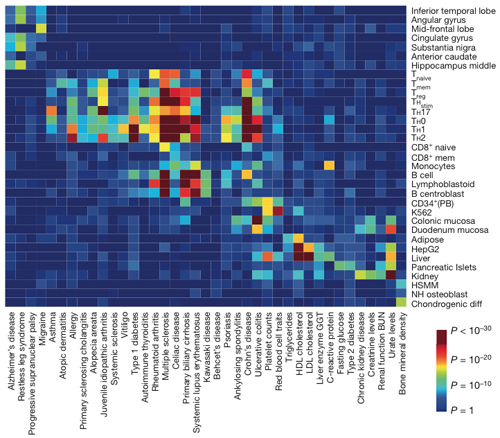

Last week, the team’s findings confirmed what many had begun to suspect. Nearly 90% of the slightly risky variants known so far for MS and other autoimmune diseases lie outside of protein-coding genes. About 60% fall on DNA addresses known as enhancers or switches, which manage gene activity in mostly enigmatic ways.

The study, published online October 29 in Nature (Farh et al., 2014), contributes a trio of research tools, developed with MS data and generalized to other diseases, said Marson, a co-first author. First, it presents a new statistical way to more finely map disease variants from high-powered GWAS with more certainty.

Second, the team created maps of the DNA regions open for enhancer activity in various types of stimulated immune cells, filling in gaps in the epigenomic data collected for human cells.

Finally, when they combined the overall genetic risk maps with the distinctive enhancer maps of immune and other cells, the researchers picked out the cells most likely at the heart of MS and other autoimmune diseases.

In a mashup of databases, MS clusters with other autoimmune diseases from asthma to ulcerative colitis based on cell types with risk factors in key enhancers. Within the immune cluster, MS displays a distinctive signature of genetic risk factors affecting selected stimulated T cells and B cells. Credit:Nature, Farh et al. (2014).

CLICK HERE to read more

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Keep CURRENT and up to date,

with MS Views and News – OPT-IN here

.

.

.

Visit our MS Learning Channel on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/msviewsandnews