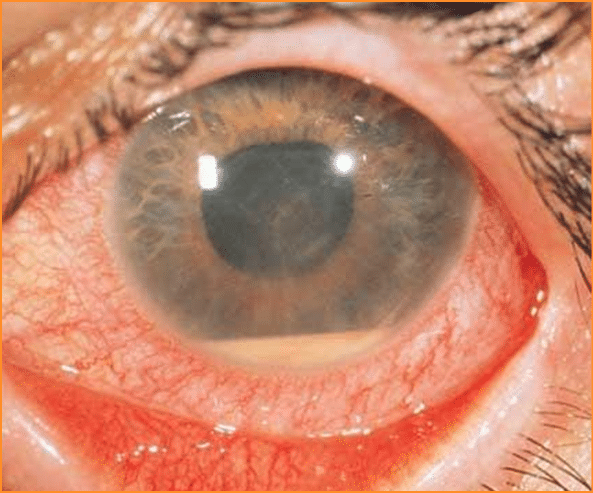

In my experience, the most common co-morbid autoimmune disease in people with MS, outside of thyroid disease post-alemtuzumab, is MS-associated uveitis.

Gavin Giovannoni May 17, 2024

Does having multiple sclerosis increase your risk of having another autoimmune disease? This is a question that is always asked. In general, the risk of having a second comorbid autoimmune disease is low. Having MS seems to protect you from getting some autoimmune diseases, for example, rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The reason for the negative association between MS and RA is likely to be related to genetic factors. The genetic factors that predispose you to MS protect you from getting RA and vice versa.

There are a few exceptions. It seems as if people with MS are at a slightly higher risk of developing autoimmune thyroid disease, both Grave’s disease and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, pernicious anaemia and uveitis. This does not mean pwMS don’t get other autoimmune diseases. I have looked after patients with MS who have comorbid RA, sacroiliitis, type 1 diabetes, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Sjögren’s syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis, autoimmune kidney disease (e.g. IgA nephropathy), celiac disease, uveitis, scleritis and myasthenia gravis. In my experience, the most common comorbid autoimmune disease, outside of thyroid disease post-alemtuzumab, is MS-associated uveitis (see below).

Having another co-morbid autoimmune disease often makes treating MS and another autoimmune disease difficult, as some disease-modifying therapies for one disease may make the other disease worse. For example, anti-TNF-alpha therapies for RA and IBD are well known to trigger MS relapses (see paper 1 below). On the other hand, anti-CD20 therapies seem to work reasonably well for both MS, RA and sacroiliitis. However, anti-CD20 therapies may make IBD worse. I have two patients with MS and comorbid IBD, who we are treating with natalizumab, which seems to be working for both conditions. The latter is not surprising as natalizumab is licensed as a treatment for IBD.

Recently, I have seen a patient with comorbid uveitis and MS. The uveitis predated their MS and was being treated with an anti-TNF-alpha therapy when they developed very active MS. Whether or not the anti-TNF-alpha therapy triggered their MS is a moot point (see paper 1 below). We elected to treat their MS with an anti-CD20 treatment based on a small case series (see paper 2 below), which suggested that MS-related uveitis also responds to anti-CD20 therapy.

They were, therefore, started on an anti-CD20 therapy that seems to be working for their MS. They became relapse-free, and their latest MRI showed no evidence of activity. However, their uveitis has now flared up, and the question is whether or not the anti-CD20 therapy for MS had negatively impacted their uveitis. We are now having to consider changing their DMT to another class to cover both their uveitis and MS. The evidence base for which DMT to choose in this patient after an anti-CD20 therapy is very poor.

Continue reading

Stay informed with MS news and information - Sign-up here

For MS patients, caregivers or clinicians, Care to chat about MS? Join Our online COMMUNITY CHAT